There are efforts taking place in Washington that would change the way the federal poverty level is calculated, and the result would be to reduce or take away necessary assistance (food, health care, etc.) from millions of people living in poverty. Every year, the federal poverty line is adjusted for inflation. The Trump Administration released a proposal this month that would use a lower inflation measure to make this calculation. A lower poverty line would make it appear that the United States has a lower poverty rate over time, but our economy and the well-being of our children and families would be weakened as millions more households struggle to afford daily life.

This proposal, if it becomes policy, would have dire consequences, including:

- 250,000 seniors and people with disabilities losing eligibility for, receiving less help from, or paying more out of pocket for Medicare coverage

- More than 300,000 children losing Medicaid/CHIP coverage and more than 250,000 adults losing Medicaid coverage

- Millions of people paying more than they can afford for their health insurance

The White House is open for comments on this proposal until June 21st. Follow this link to learn more and have your voice heard on this critical issue.

Why and how we measure poverty

At the country, state and even local levels, it’s important to know how many people are living in poverty. An accurate measure of poverty helps decide how many people need anti-poverty programs, how much money to put toward them, and where to locate them. Over time, it tells us if targeted policies and programs are working. And, simply put, if we didn’t measure poverty, it would be too easy to forget those living in the thick of it.

There are legitimate criticisms of the Official Poverty Measure (OPM). For one, it is calculated using an outdated formula that fails to capture the experience of living in poverty in the United States. But the administration’s proposal to change the way we calculate the poverty threshold ignores the OPM’s shortcomings and focuses only on inflation. This approach misses the forest for the trees, and its practical impact would be to take away critical supports, like health care, from hundreds of thousands of people.

The Social Security Administration established the current poverty measure in 1964. Using the data available at the time, they found that families spent one third of their income on food on average. Thus, the OPM was set by taking the cost of a minimum food diet, multiplied by three, and adjusted for family size.

The need for change

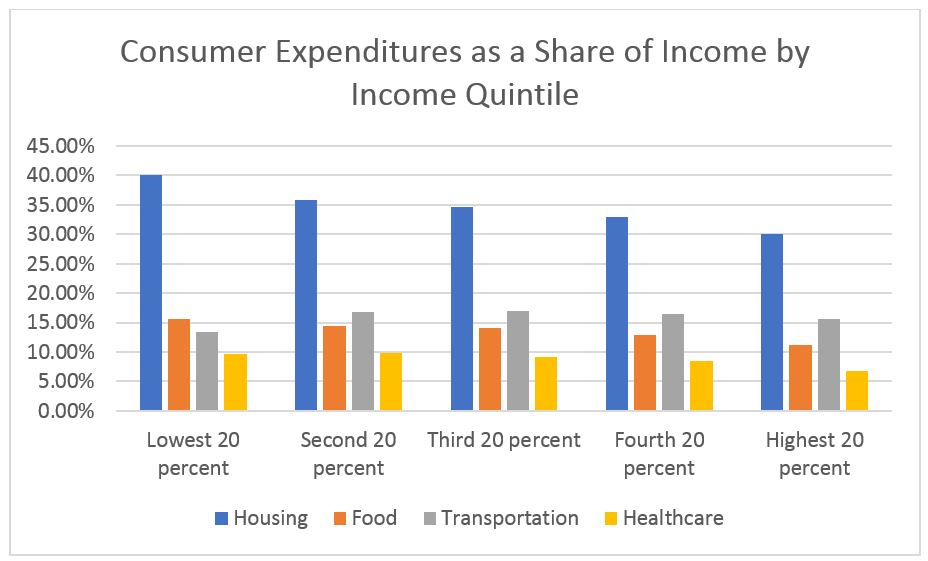

The economy and consumer spending patterns have changed since 1964. In the past 55 years, food costs as a share of family budgets have declined, but housing, transportation, and health care costs have all increased. Calculating poverty based on the original formula is inadequate. In fact, these concerns lead to the introduction of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) in 2010. The SPM sets poverty levels based on expenditures for food, clothing, shelter, and utilities.

The SPM did not replace the OPM for the purposes of determining poverty statistics or means-tested program eligibility, but it does represent a good-faith attempt to accurately represent poverty as its experienced by American families.

Missing the mark

The administration’s narrow focus on the appropriate way to measure inflation does not address the real criticism of the OPM. The proposal would change the metric we use to measure inflation from the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (CPI-U) to the Chained Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (Chained CPI-U). Many economists argue that Chained CPI-U is a better measure of inflation than CPI-U because it accounts for substitutions between goods. For instance, if the price of beef increases and consumers respond by purchasing more chicken instead of beef, grocery bills overall will go up less than the inflated price of beef. That means that inflation grows more slowly over time, which is why the official poverty rate would nominally climb more slowly if this change were enacted.

While this may be a more accurate measurement of inflation for the broad economy, it is unlikely to more accurately capture the spending habits of low-income families. Research indicates that lower income families experience higher rates of inflation. That’s probably because families at different income levels expend different portions of their budget on different goods:

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Surveys (2017)

If anything, the evidence suggests that the United States sets our poverty levels too low. Most developed countries measure poverty by setting it at 50% of their country’s median income. For the U.S., that would be roughly $30,000 a year for a family of three based on 2017 income[i]. That’s about 50% higher than the OPM for a family of three that year, $20,420. A 2016 survey by the pro-market American Enterprise Institute found that most Americans put the poverty level for a family of four at around $30,000. That’s 25% higher than the official poverty level that year for a family that size.

There is little justification for recalculating the OPM using a different measure of inflation unless a more holistic reimagining of poverty is undertaken at the same time. Without that, this seems to be little more than an attempt to reduce outlays on public assistance programs.

[i] Author’s calculations based on median household income and average household size Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Average family size rounded up to 3 from 2.54